Commoditization, Innovation, and “Transformation” — Through the Lens of Box

In an interview with the Wall Street Journal prior to their mid-January 2015 IPO, Box’s CEO Aaron Levie was asked, “Is online file sharing a commodity?” Levie hedged the answer, offering only that “the storage component of what we do is a commodity product.” But, in truth, storage alone has long been undifferentiated. (Thumb drives, anyone?) What Levie hesitated to say, but assuredly knows very well, is that the general category of “enterprise file sync and share” (EFSS) has also largely been commoditized. That, after all, is why Box has been trying to shake off the straightjacket of EFSS for some years, and why it described itself in SEC filings as an “enterprise content collaboration platform.” Levie added: “All our innovation is at the layer above the raw material” of commoditized content storage.

Box’s efforts to elude commodity status provides an excellent case study of the role of commoditization and innovation in the age of digital disruption and the resulting need for fundamental business transformation. In order to understand the positives of the (potential) innovation upside – for Box as well as many, if not most, other companies – it helps to first tarry with the negative aspects of commoditization that this innovation agenda is meant to dispel.

Box’s efforts to elude commodity status provides an excellent case study of the role of commoditization and innovation in the age of digital disruption and the resulting need for fundamental business transformation.

What becomes a commodity most?

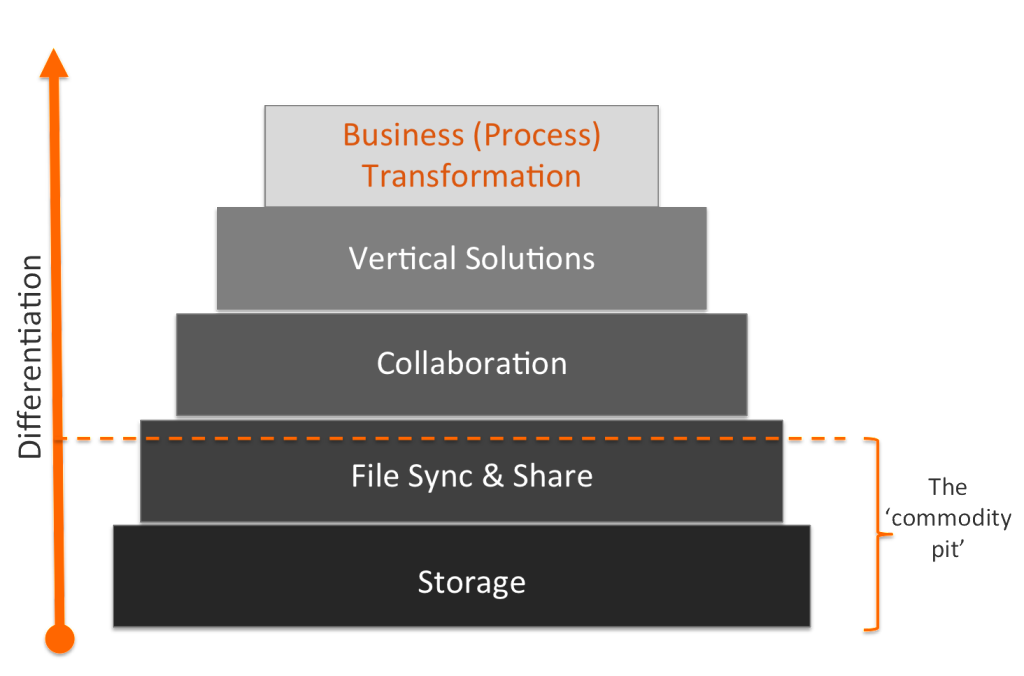

Consider a simple linear depiction of differentiation:

At one extreme is utter lack of differentiation and ubiquitous consumer/buyer choice. Think of a humble cup of coffee, which you can get anywhere, including your own home or office. At the other end is total differentiation — the utterly unique offering that (crucially) also has widespread appeal. (In my experience as an analyst, such offerings exist almost exclusively in the fantasies of those vendors and service providers who assert that they have no competitors. If true, this usually means that they also have no customers.)

Despite the common definition, commoditization isn’t located simply at the first extreme. This is largely because providers can and will spend to create the illusion (and thus the effect) of difference. The traditional method for differentiating commoditized products is branding — think of Pepsi or Coca-Cola versus any number of generic colas. The more recent and now very popular strategy is to differentiate on the basis of experience — both Starbucks and Nespresso have done so with the humble cup of coffee. But somewhere along the line — the location depends on the type and maturity of the product category, the number of competitors, and the determination (or imprudence) of one or more providers to “buy” differentiation — lies the point where differentiation is commercially unviable. This point defines the division between commoditized and differentiated offerings in a given category.

Innovating against commoditization

Levie’s lurid footwear aside, branding and customer experience are of limited value for Box. Rather, as Levie noted, the company seeks to resist commoditization (and the price wars and narrow margins that follow) through innovation — that is, by creating genuinely differentiated products. If commoditization is a kind of entropy — “the tendency for all energy products and services in the universe to evolve toward a state of inert uniformity” — then innovation is the application of work to maintain order and preserve the business model. (And radical innovation — that is, self-disruption — is the creation of a new business model.)

If commoditization is a kind of entropy — “the tendency for all energy products and services in the universe to evolve toward a state of inert uniformity” — then innovation is the application of work to maintain order and preserve the business model.

If we stand up the spectrum of differentiation against Box’s proposed innovation strategy, we can clearly see how this is supposed to work.

There are a few necessary provisos about this graphic. First, the division between commoditized and differentiated elements/features is, in fact, not a sharp line but a fuzzy and permeable border. For example, Box’s EFSS solution contains some distinctive features (like the new enterprise key management), just as their emerging collaboration capabilities will necessarily offer many services that are effectively undifferentiated among numerous vendors.

Second, I stress that this is my representation of Box’s product strategy, but I believe it is a fair one, based on the pronouncements of Levie and other Box executives. In particular, the aspiration to enable “business transformation” has been embraced by Box, as we will see in a moment. In fact, I think that the notion of offering — or rather, enabling — business process and wider business transformation (beyond transforming the way people work) is one that Box should and, arguably, must aim for, for reasons that I’ll explain below.

Finally, when I speak of business (process) transformation, I am referring to the perceived need for companies of every size and description to fundamentally reform and transform the organization and its value-producing processes in light of digitization and consumer empowerment. By analogy, this is a question of the business as an organism adapting to a profound shift in the environment in which it operates (and hopes to thrive). This usage is related to, but should not be confused or equated with, the established practices subsumed under business process management (BPM), such as business process improvement (BPI), business process reengineering (BPR), and business process transformation (BPT). (For more on the imperative for wider sense of business transformation, see this podcast and this DCG Insight Paper.)

The limits of innovation

There’s only one thing wrong with the time-honored effort to counter commoditization with innovation— and that is that it’s time-honored, widespread, and common. It’s tempting to say that product innovation as a response to the threat of commoditization has itself become a commoditized strategy. Practically speaking, this means that Box’s competitors will almost certainly pursue a similar course. In that case, Box has some advantages — over, say, Dropbox — by virtue of a considerable head start as an enterprise solution. Also, Box’s vertical solutions seem (or at least promise) to be serious — much more than the typical, and largely useless, vendor “kick start programs.” But Box is also at a disadvantage compared to some competitors — say, Google or Microsoft — that have immeasurably larger development resources, and might (I stress might) be willing to accept much smaller margins, or even losses, in the evolving EFSS space in order to secure clients for auxiliary products and services. (For more on this threat and other aspects of Box’s competitive position, see Jonathan Vanian’s excellent analysis.)

“Land and expand” and/vs. “inform and transform”

However, I think Box’s more interesting challenge is inscribed right at the heart of the innovation strategy. In the WSJ interview, Levie said, “We’re just on the 1.0 part of our business model right now, which is land the deals, and then we expand the deals and begin transforming the customers.” (Emphasis mine.) I think this statement contains the key insight about how Box’s innovation strategy might deliver a distinctive competitive positioning, if not exactly a sustainable competitive advantage.

In contrast to the cumbersome alternatives (email), or the ugly and user-hostile enterprise systems (document management solutions and early collaboration tools — yes, I’m talking about you, MOSS), Box was from the beginning like opium for the oppressed masses of knowledge workers.

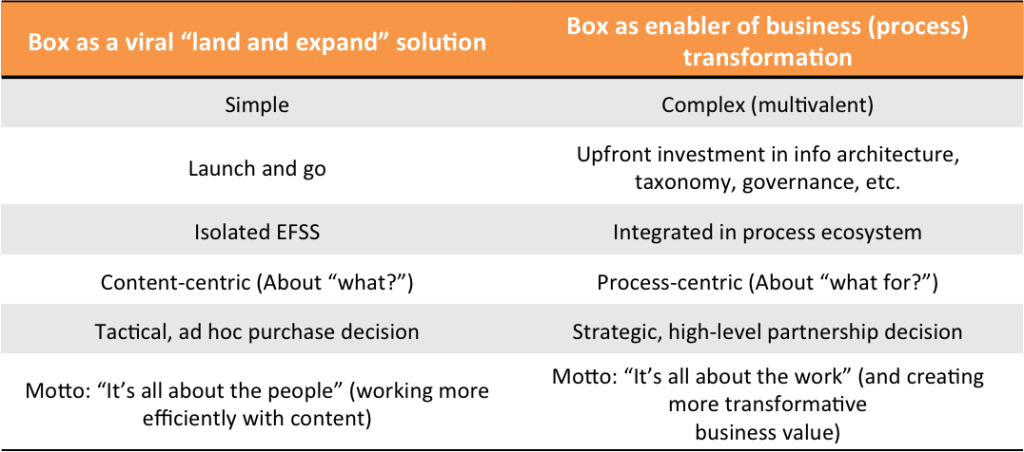

First, I think what Levie means is that “land and expand” is the 1.0 part of the business model. This approach has defined Box from the start; in fact it is something like the founding vision of the company: Provide a simple, attractive, user-friendly, intuitive way to store and share content. In contrast to the cumbersome alternatives (email), or the ugly and user-hostile enterprise systems (document management solutions and early collaboration tools — yes, I’m talking about you, MOSS), Box was from the beginning like opium for the oppressed masses of knowledge workers.[i]

Unsurprisingly, addiction and viral adoption is the typical result. From a cheap (or even free) solution for a few team members, Box frequently grows to support a larger project group, a department, a line of business, a geography, etc. Box’s unmatched success with viral expansion — specifically, with user-driven expansion among employees, based on attractive, “consumerized” user experiences — has powered its growth, justified the attention it has garnered, and propelled it to the IPO. And from the Street’s perspective, it is precisely this demonstrated ability to grow a “cohort” of customers (such as all those signed in a given year) with year-over-year increases in annual recurring revenue (ARR) that justifies Box’s growth narrative.[ii]

But despite Levie’s formulation, I don’t think that “transform” is simply the next, organic, phase after “land and expand.” If “inform and transform” is a fair way to characterize the “2.0” part of Box’s business model, then it is important to identify and understand 1) how this transition can — or might not — take place and 2) what it entails for Box’s innovation strategy.

The burdens of the past

As noted, once Box lands in an organization, employees, in most cases, and much to Box’s credit, take to it like flies to a dropped piece of candy. Precisely that initial “viral” success, however, can hamper and inhibit the “transform” phase as envisioned by Levie. When people are using Box happily and widely — but often “wrongly,” because the use is intuitive and without governance, or architecture, or alignment with high-level customer experience goals — then shifting them, along with the structures, nomenclatures, and habits they have built up, to a rationalized, strategic use becomes much harder. In short, Box’s functional advantage (ease of use and rapid adoption) might hinder their strategic goals (fundamental business process transformation).

In short, Box’s functional advantage (ease of use and rapid adoption) might hinder their strategic goals (fundamental business process transformation).

In fact, “land and expand” and “inform and transform” appear to prescribe two different sales strategies, account management approaches, and product development roadmaps — in short, two different sets of incentives.

For Box to survive and thrive amongst the software giants and numerous emerging competitors, Levie’s phrase “transforming the customers” has to indicate far more than the cost-saving goals of making knowledge work more efficient and reducing spending on legacy collaboration platforms. In my view, it has to mean what it literally says: Helping companies make the fundamental process and organizational transformations that are necessary if they are to compete — indeed, if they are to survive — in this rapidly changing, consumer-centric business environment.

As the ability to offer distinctive and attractive customer experiences moves from competitive advantage to competitive prerequisite—– in other words, as differentiated customer experience becomes a commoditized attribute that consumers expect and demand — companies of all types and sizes need to rethink and redesign not just content and collaboration workflows or isolated business processes, but the entire business as a process for conceiving, creating, and delivering coherent and consistent experiences. It is, to put it all too simply, the difference between transforming the way a company works and transforming the work of the company. (Or even, making transformation the work of the company.)

Crossing the chasm

Box’s innovation roadmap aims to ensure that it matures into phase 2.0 of its business model. (And beyond that, with luck, into 3.0, 4.0, and . . . n.0.) This isn’t, however, a “natural” progression. Or rather, it is a natural and common transition that most humans have experienced, and, often, suffered through — namely, adolescence and the passage into adulthood.

I hesitate to use this analogy, since there have already been far too many unjustified jabs at Levie and the other “kids” at Box. The age of this or that executive or product manager is irrelevant. The point is that Box as a company grew up and thrived with a business model based on easy sale and viral adoption (and viruses are by definition unchecked and ungoverned), and a product strategy based on simplicity, and ease of use.

There is, however, nothing simple, easy, or intuitive about how companies can (try to) survive in the face of digital disruption and the age of the customer. For Box (and equally for most of its competitors), that’s a different world, a different business environment, a different set of problems to be addressed. “Land and expand” remains, for now, critical to the company’s growth — and to its stock price. But in order to (help) transform customers, what Box needs to “expand” in an organization is no longer (only) the usage but also, and far more importantly, the use cases — and to ensure that these are connected and integrated to form the system that powers what Geoffrey Moore calls customer “systems of engagement.”

It may well be that the most critical innovation — for Box and for its clients — is not the equipment (a product feature or add-on module) but rather Box’s nascent and — so I’m assured — rapidly growing consulting services.

All of the recent product and partnership announcements around collaboration, workflow, vertical solutions, enhanced security, new integrations, etc. indicate that Box’s leadership wants to be equipped for this transition. But it may well be that the most critical innovation — for Box and for its clients — is not the equipment (a product feature or add-on module) but rather Box’s nascent and — so I’m assured — rapidly growing consulting services. This is not only because of the widespread recognition that people and processes trump technology, but increasingly because what matters most in the processes is not efficiency but empathy, experimentation, creativity, and systems thinking.[iii]

It is the difference between nurturing and growing plants wherever and whenever they naturally emerge and designing an elaborate, complex, yet unified and beautiful garden from the outset.

Partnerships — deep, meaningful, strategic partnerships — can also be significant innovations. But it was striking that Levie’s blog post about the recent Box-IBM partnership highlighted only Box’s combination with “IBM’s impressive portfolio of leading security, analytics, content management, and social capabilities” and the option to store data on IBM’s cloud. What of IBM Global Services, which could magnify Box’s consulting resources by several orders of magnitude? What of IBM’s impressive investments in design and design thinking, which are exactly the approaches and tools that any consulting team should deploy to plan and create consistently compelling experiences? Global Services warranted a mention on the (perhaps temporary) partnership web site, but as Levie’s blog indicates, consulting is not the lead story. By continuing to concentrate on technical aspects and the desire to “transform work in the cloud” (my emphasis), Box will remain at, say, phase 1.5 of the company’s “defining strategy.”

I’m fond of mocking the constant use of “It’s all about the people” by advocates of collaboration and enterprise social (among whom I count myself). But as innovation in the form of rapid and incessant business (process) transformation becomes requisite for continued existence as a commercial entity, much will indeed depend upon those people — on the side of a solution provider like Box, on the side of third-party service providers, such as IBM Global Services, agencies, and consulting firms, and on the side of the client organizations — who plan, build, and operate the underlying flexible, responsive platform for business transformation.[iv]